A School District In Crisis

Detroit’s Public Schools 1842-2015

Purchase this report as a beautiful hardcover book for $100.

Limited edition with 20 extra pages of reporting and photography including

- Historic and contemporary pictures of Detroit’s Public Schools

- Additional commentary on the future of the school district

Pay What You Want

We made this independent report because we thought it was important. If you agree, please share it and consider contributing $1 or more. If we reach $25,000, we'll keep doing more work like it. If you have questions or would like to commission a report on any topic, email us at team@makeloveland.com. Thank you, and please enjoy.

A Report By Loveland Technologies

Authors:

John Grover

Yvette van der Velde

MADE WITH LOVELAND

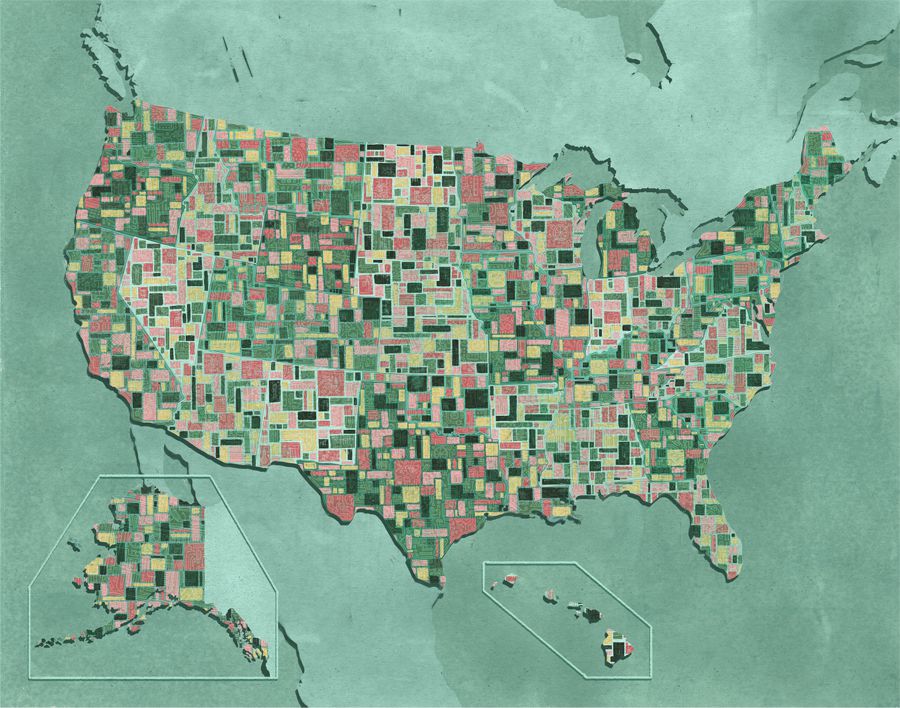

Loveland Technologies is a Detroit-based company creating a public database of every property in America, along with tools for understanding and improving land use. This report was prepared using our Regrid system for mobile and desktop property data collection and analysis. To use Regrid for a project of your own anywhere in the country, see regrid.com. To consult with LOVELAND call us at 888-4RE-GRID or email help@regrid.com.

Introduction

This report is the result of 18 months of research, examining 200 years’ worth of documents and records, and visiting every school in Detroit to establish a comprehensive look at the entire history of the school district and how the repercussions of decisions made in the past are still being felt today.

This report covers three specific topics:

- A detailed history of every public school in the city, including the school’s location, opening / closing / demolition dates, and other historic details of note

- A physical survey conducted of all school locations by a Loveland surveyor who took detailed photographs and extensive notes of their current condition / use

- An analytic look at how the school district has grown and shrunk, examining the underlying factors behind opening and closing schools

Executive Summary

The goal of this report is to address a simple question: What happened to Detroit Public Schools?

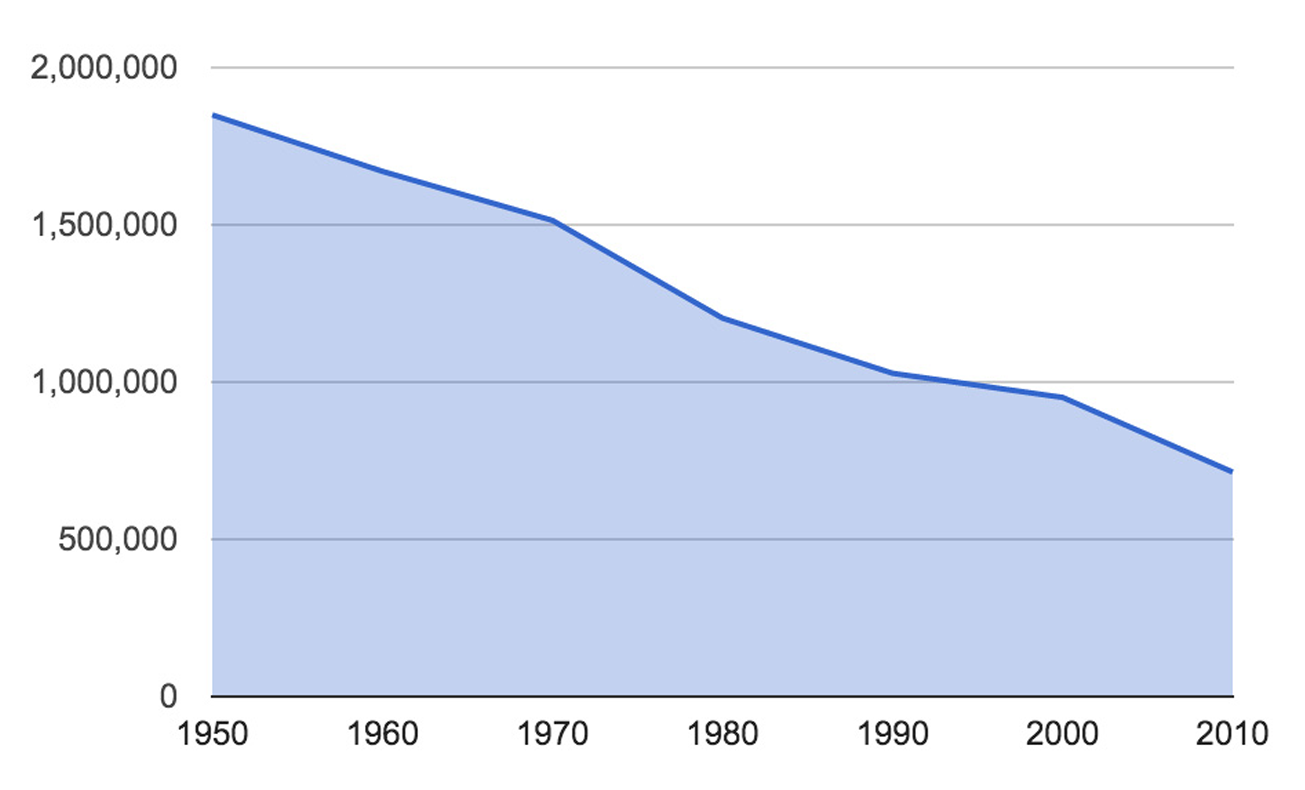

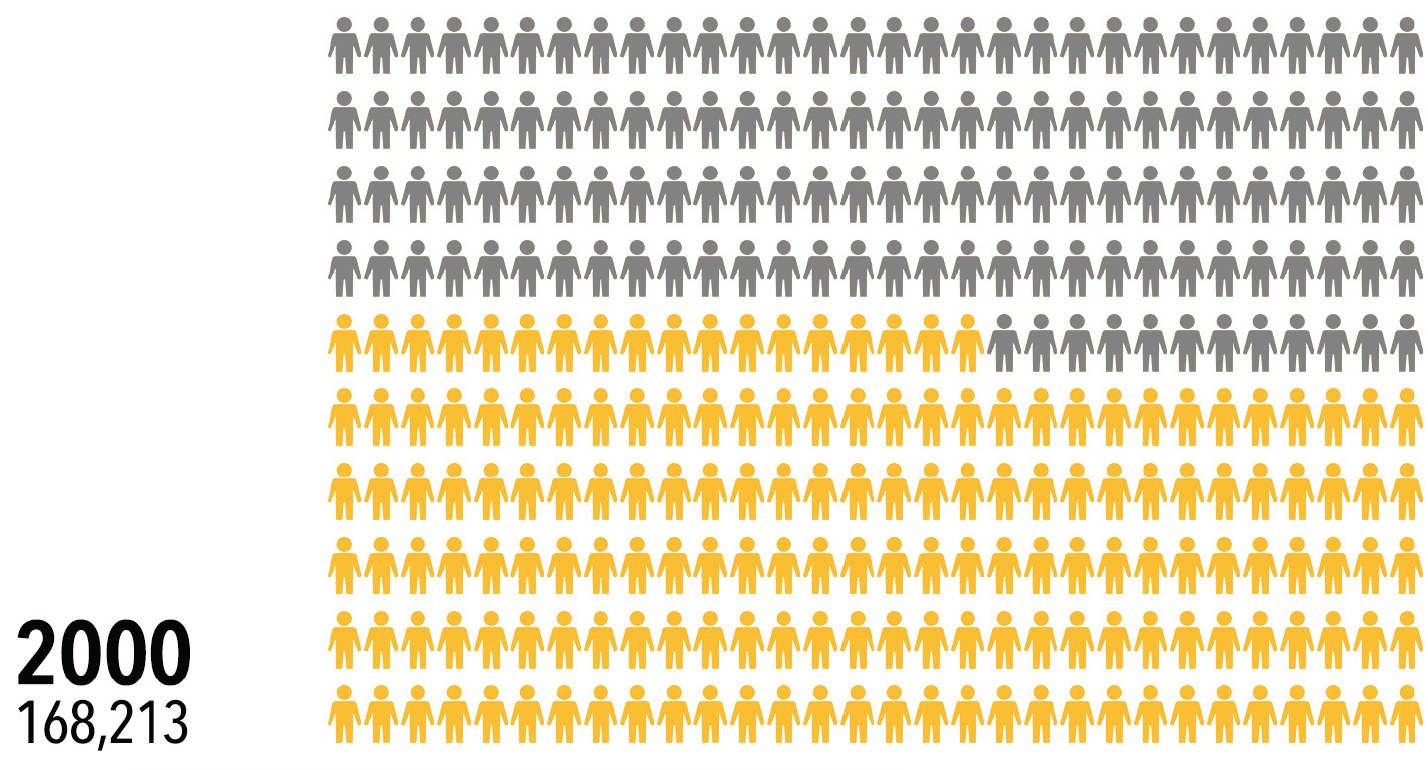

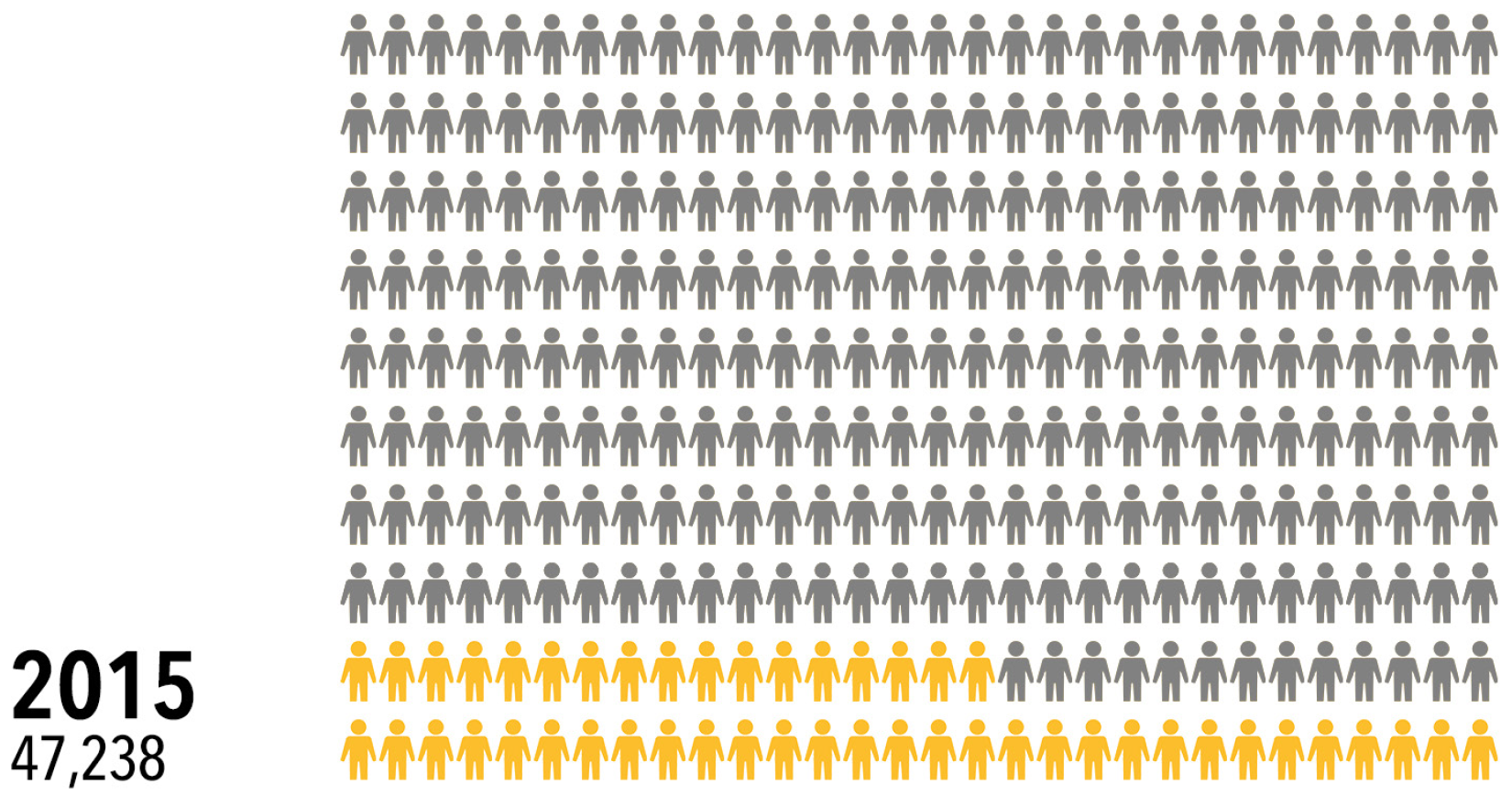

Since the school district's peak in the 1960's, enrollment in DPS has declined as the city's population has dropped and parents have opted out of public schools. Just 47,000 students attend public schools in Detroit today, down from nearly 300,000 in 1966. Nearly 200 schools have closed in the last 15 years. The city’s neighborhoods are dotted with vacant, abandoned schools and empty lots where schools once stood.

The situation the district finds itself in today is the culmination of a long series of decisions and events, dating back to the start of public education in Detroit nearly 200 years ago. It's a complicated history of rapid expansion followed by equally rapid decline that closely follows the trajectory of the city.

The academic landscape of the city has undergone tremendous change over the last 30 years. Public schools now face competition from charter schools and neighboring suburban school districts, putting them under severe financial strain.

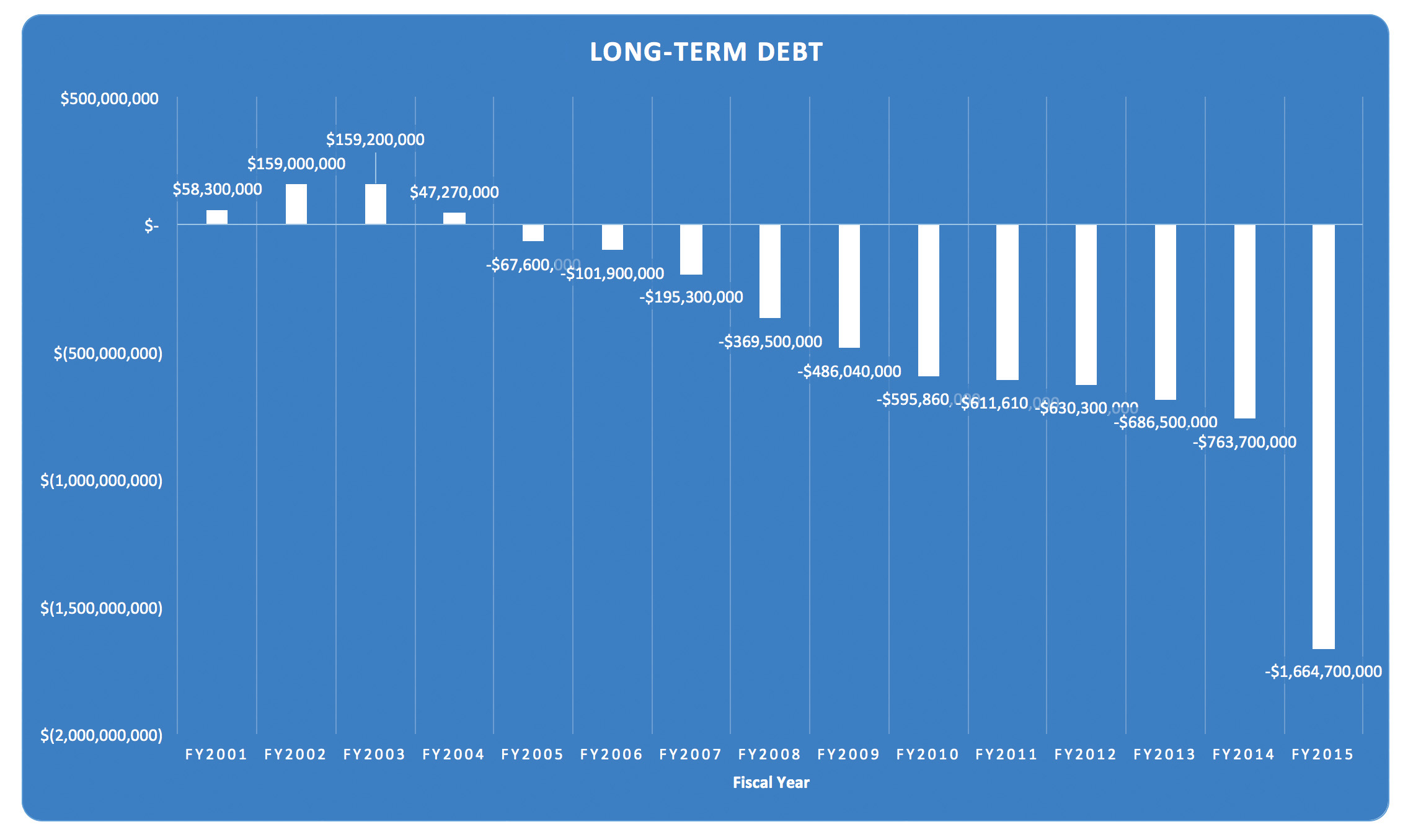

Since 2009, DPS has been under the control of state-appointed emergency financial managers. The cumulative impact of them has been questionable at best. Despite modest improvements in test scores, enrollment has plummeted and schools have closed while the district's financial situation has only worsened. Under emergency financial managers, the district has run at a budget deficit that now tops $300 million dollars, with long term debts of over $3.5 billion dollars.

The resulting morass has left DPS trapped in a cycle of student loss and school closure that, if left unchecked, will result in bankruptcy in the next few months, and the likely dissolution of the school district in a matter of years.

This report looks at the complete history of the Detroit Public Schools, and how decisions made five, ten, even 100 years ago are having significant consequences today.

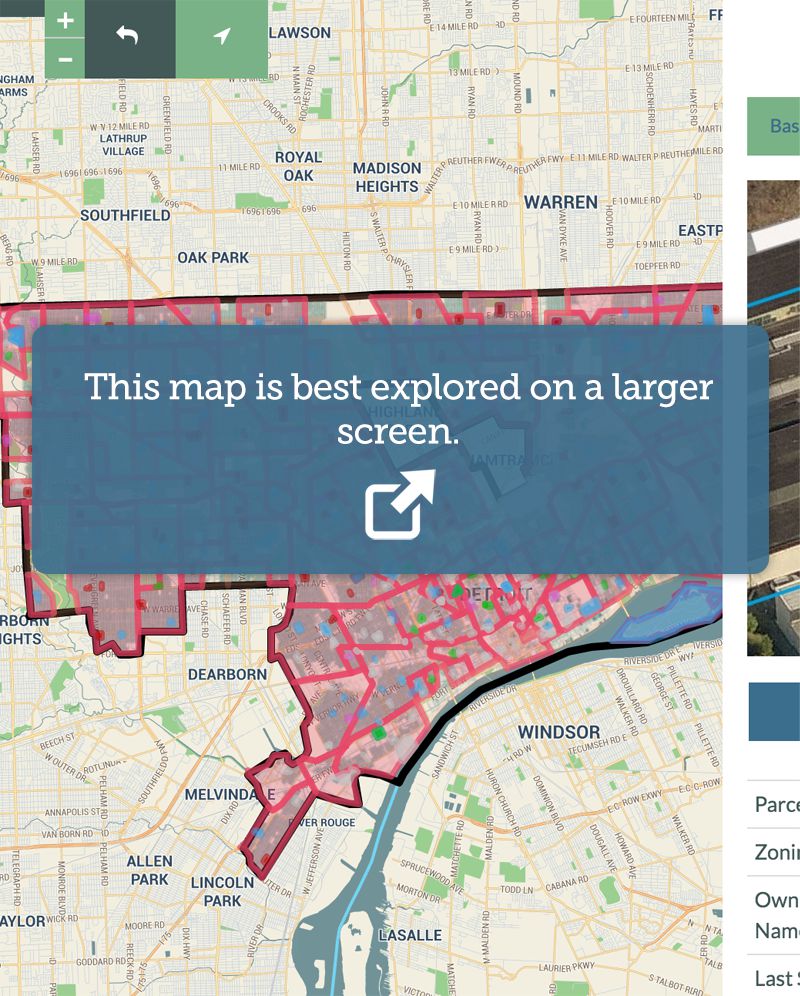

This map shows locations, pictures, and historical narratives of every public school in Detroit going back to 1842.

What happened to Detroit’s Public Schools?

Over the last 20 years, public school districts across the country have closed buildings in response to budget cuts, population shifts, declining enrollment, and alternative education systems. Many of the school closings are located in older urban centers like Philadelphia, Chicago, and Detroit, which have struggled to adapt to an evolving education market where public schools are no longer the only option.1

Today public school systems compete with state-funded private schools, parochial schools, and other nearby public school districts for students and funding. People moving from city centers to suburban areas have left older schools underutilized, straining already tight budgets.

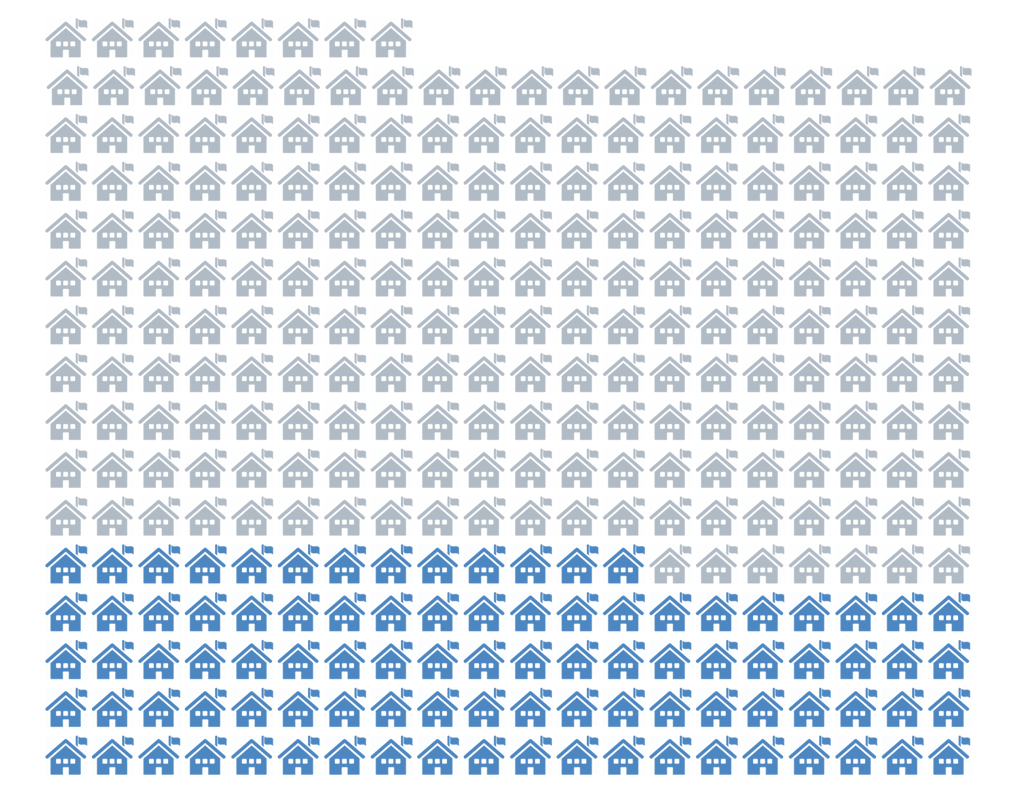

From the City’s Peak in the 1960’s:

213 Public Schools Have Closed

84% Decrease in Public School Enrollment

1.15M People Have Left Detroit

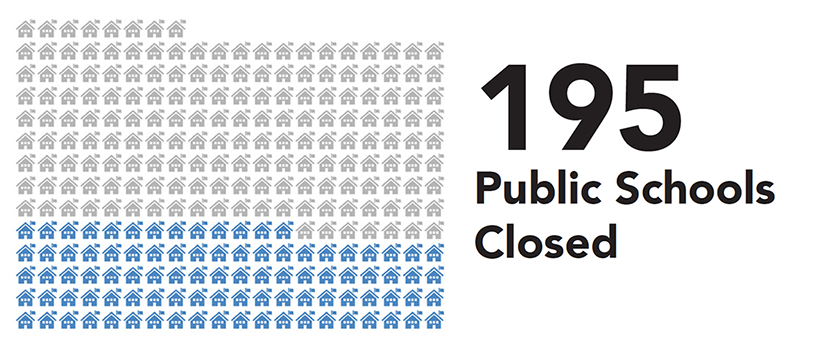

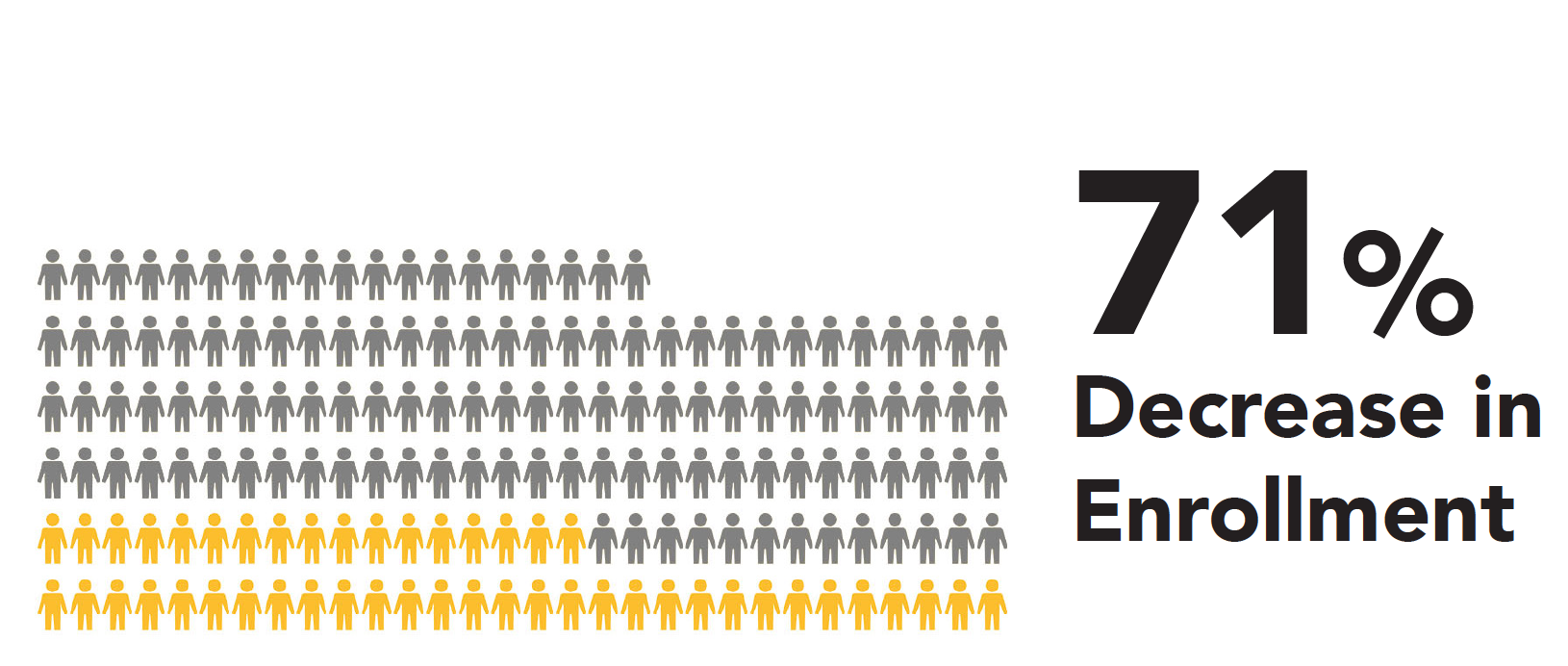

Between 2000 and 2015, 195 Detroit Public Schools closed as enrollment fell from 162,693 students to 47,959, a decline of 71%.2 There are 93 active school buildings today, compared to over 380 in 1975.3 Many of the remaining schools are under capacity, with aging infrastructure that makes them expensive to operate. Enrollment is expected to continue to drop.

Each closing has been a difficult decision, with political, social, and economic consequences that extend outward from the neighborhood into the city. Students need to be moved into different schools, often over the objections of parents and teachers, while surplus buildings need to be disposed of through sale or demolition. The sheer number of schools closed in such a short period of time has created a situation where questionable decision-making has compounded financial problems, increasing the number of closings exponentially.

The landscape of the city is dotted with closed school buildings. They range from tiny prefab classroom trailers to sprawling Mediterranean castles, many of which have been broken into and looted of anything of value. Vast empty lots in the center of neighborhoods mark the location of schools that have been torn down, leaving holes in the communities where they once stood.

How did Detroit’s public education system get to this point? What has the impact of school closures been on the residents, neighborhoods and City of Detroit? What happened to these buildings? And what is the outlook for public education in the city?

Students standing in front of the entrance to Cooley High School.

Early History

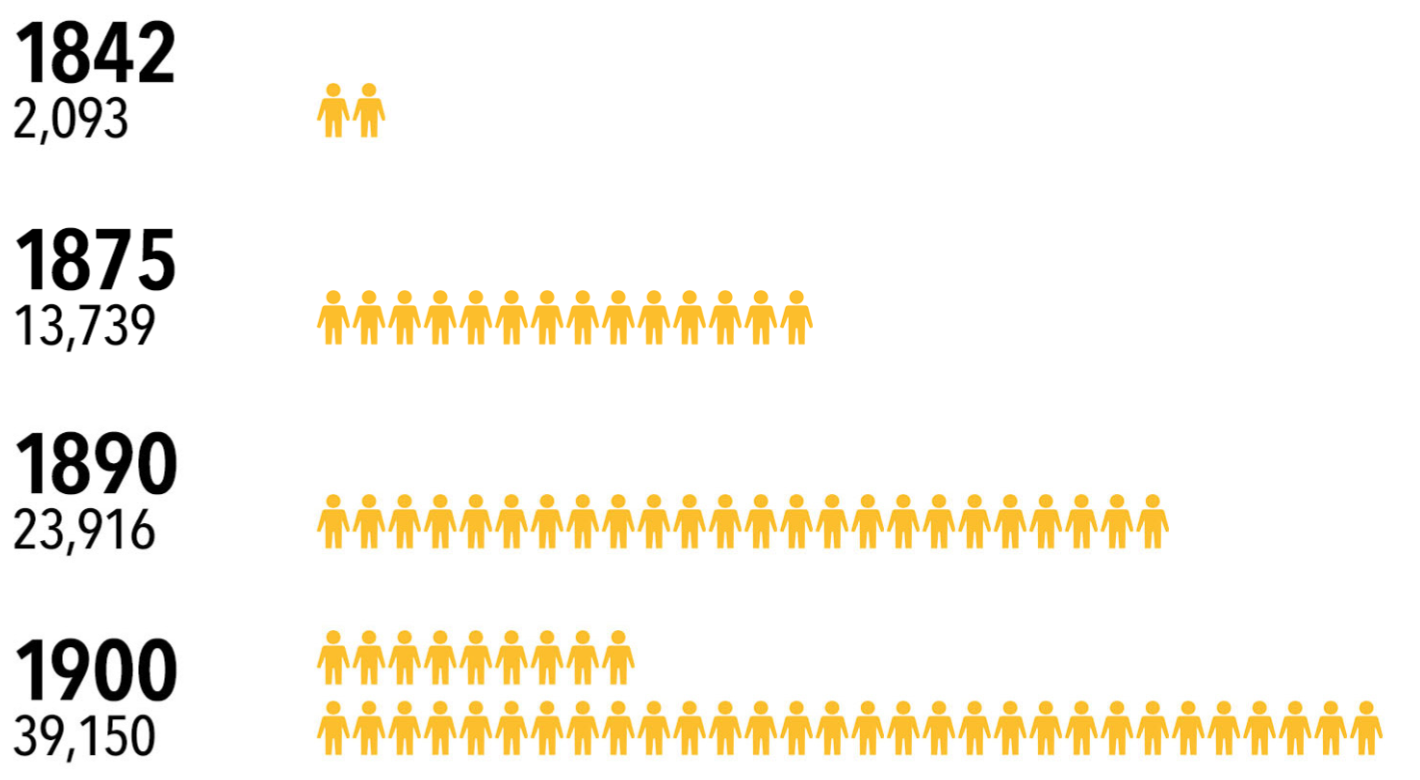

In 1827, the Michigan Territory enacted a law requiring that all townships with 50 residents or more have a school. Early formal education in Detroit consisted of “common” or “free” schools, which were run by individuals or religious organizations. As the city grew, these schools became organized into districts or wards.4 By 1840, Detroit was a city of 9,102 residents, with about 2,000 school-aged children. An early history of the schools states: “...the real estate and personal property of eight School Districts in this old and respectable city should be summed up in one common schoolhouse erected on leased ground, and a few old desks and benches scattered about in hired tenements...”5

Education in the 1800’s was primitive by today’s standards; students from all grades shared cramped quarters in a single room, often with a coal stove in a corner to provide heat. Teaching standards varied depending on the school: “Reports of the board show that there was so little uniformity in teaching that it was impossible to transfer a child from one school to another without loss of time which in many cases amounted to more than a term’s work.”6

“In education, as in politics, business and other phases of social life, we are now passing through a period of transition. Old ideas, theories, and methods have been outgrown; society is daily making new and greater demands upon the school...”

— Arthur Moehlman, Public Education in Detroit, 1925

In February of 1842, the Detroit Board of Education was created by the State of Michigan to oversee and manage the city’s publicly funded schools. Within a year the district had 13 schools operating out of houses, storefronts, and church basements.7 Finding adequate housing for students was a constant problem; of the 15 school buildings used by the district in 1852, only two were built for the purpose of education - the rest were rented rooms, houses, or other buildings that had been converted into schools. The 1852-53 annual report notes that “In the Eighth Ward we own a small house on Seventh Street, in which about two hundred usually crowd themselves, literally upon one another.”8 By 1867 schools had switched over to a half-day schedule, as there were only 5,896 seats for the 20,353 school-aged children. Over 1,500 students were turned away for lack of seats.9

To keep up with the growth of the city, the Board of Education built 88 schools between 1856 and 1900,10 spreading outwards from the city center into the surrounding areas. The new school buildings reflected the evolving attitudes towards education, increasing classroom sizes, diversifying course offerings, and improving sanitary conditions. These schools also played an important role as the social center of neighborhoods, being used for meetings, neighborhood events, and even as churches on the weekends.11

Growth

Detroit’s first brush with the horseless carriage came on a cold, snowy night in March of 1896. Amid clouds of smoke and loud commotion, Detroit’s first automobile eased out of a workshop onto St. Antoine Street. Behind the tiller was Charles Brady King, the designer and builder of the four-cylinder carriage.13 14 The drive around the dark streets of the city was brief, covering a few blocks before the engine broke down, but it was official: the age of the automobile had arrived in Detroit.

No other industry has had such an impact on the course of Detroit like that of the automobile. Though the city had a fairly diversified economy at the turn of the century, the auto industry would grow to dominate the economy of Detroit, and with it the fortunes of the city would rise and fall.

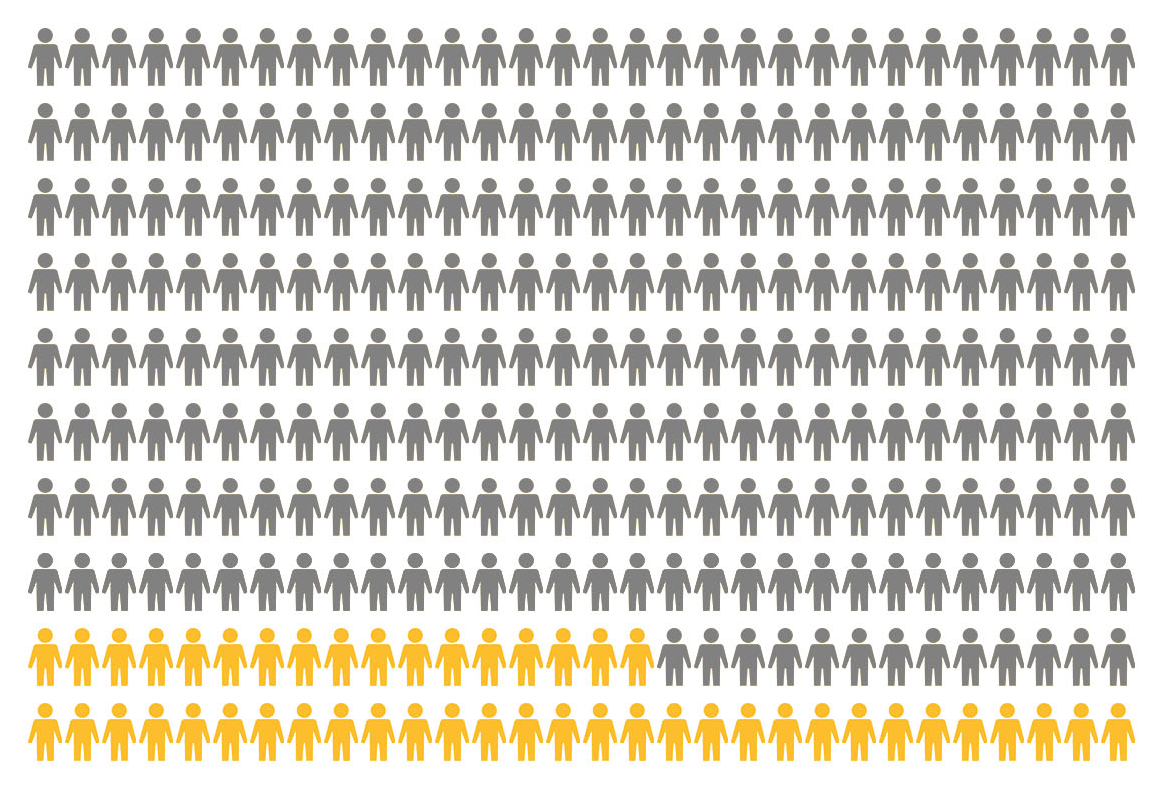

In just 30 years, Detroit’s population increased from 285,704 in 1900 to 1.57 million in 1930, as immigrants from across the country and around the world flocked to the city to work in the automobile plants.15 As the population boomed, enrollment increased in Detroit’s public schools from 13,739 to 39,150 students by 1900.16

Growth of the Early School District

From 1842 to 1900, enrollment in Detroit’s public schools grew from 2,000 to nearly 40,000 students. Each figure equals 1,000 students.

Trowbridge School, built in 1860.

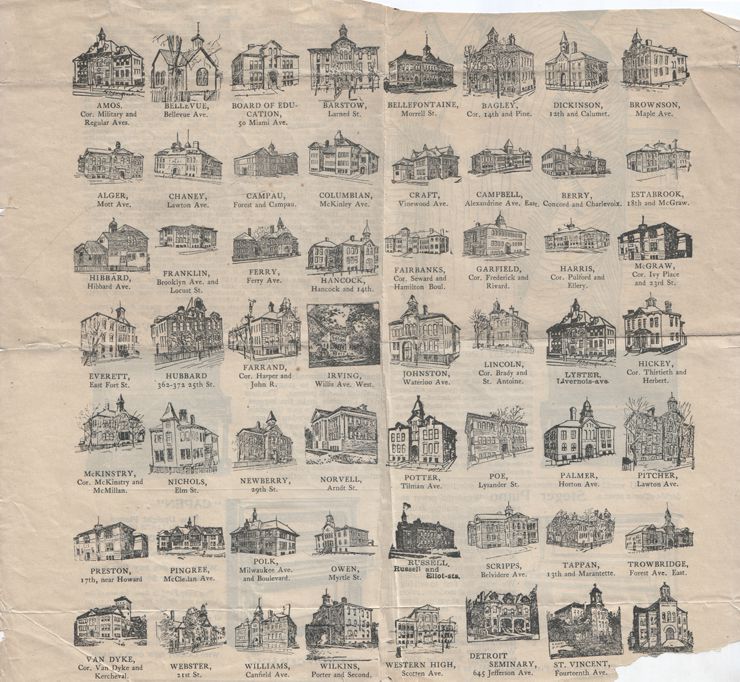

Detroit’s schools in the early 1900’s.

“Despite all efforts to build schools, there has scarcely been a year in the past fifty when the Detroit Board of Education really could boast of adequate housing facilities for the City’s boys and girls of school age.”

— Detroit Public Schools, 1950 annual report

The jump from sleepy city to industrial metropolis far outstretched the resources of the already overburdened school district. Enrollment grew 10% every year between 1912 and 1918, sending administrators scrambling to add more schools.17 Schools built in the 1860’s were no longer adequate, and over 60% of students were in “poorly lighted and poorly ventilated basement rooms, in three-story buildings 50 years or older that were grave fire hazards, in crowded classrooms, or on part time.”18

180 new school buildings were built between 1910 and 193019 until the onset of the great depression slowed population growth. New schools were also added to the city as it expanded its borders, annexing neighboring villages and townships through the 1800’s and early 1900’s. Forty-two school buildings and their students were annexed to Detroit between 1916 and 1926.20 The city grew with such speed that some schools were annexed as they were being built, with the new school district finishing construction.21

Students in a temporary classroom located in a church.

Peak and Decline

Detroit’s population peaked in 1950 at 1.85 million, as the Second World War brought an influx of residents to the city to work in the factories of the “arsenal of democracy,” and afterwards, veterans coming home from the front. Enrollment in Detroit Public Schools continued to climb as well, passing 200,000 students in 1927, and 250,000 in 1952.23 Unlike older cities like Chicago and New York, Detroit’s growth period came at a time when car ownership was more affordable, and as a result workers could live further away from the factories and commute to work. Instead of growing upward with high-rise apartment buildings, the city grew outward, with rows of single-family homes stretching for miles outside of downtown.

The movement of families from the inner city to the outer edges presented a complex challenge to the school district: building new schools in new neighborhoods, and rebuilding older schools closer to downtown. Starting in 1947, construction focused on building smaller, neighborhood schools that could be added onto easily as a neighborhood grew, so that children in any part of the city would have a school in walking distance.24 Older schools were remodeled or replaced with newer buildings, part of a project that would extend into the 1970’s.25

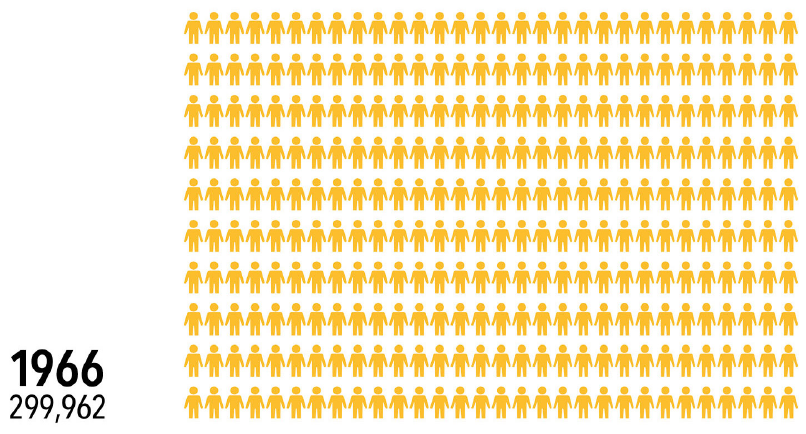

Peak enrollment was reached in 1966, with nearly 300,000 students attending over 370 schools throughout the city.

Decline

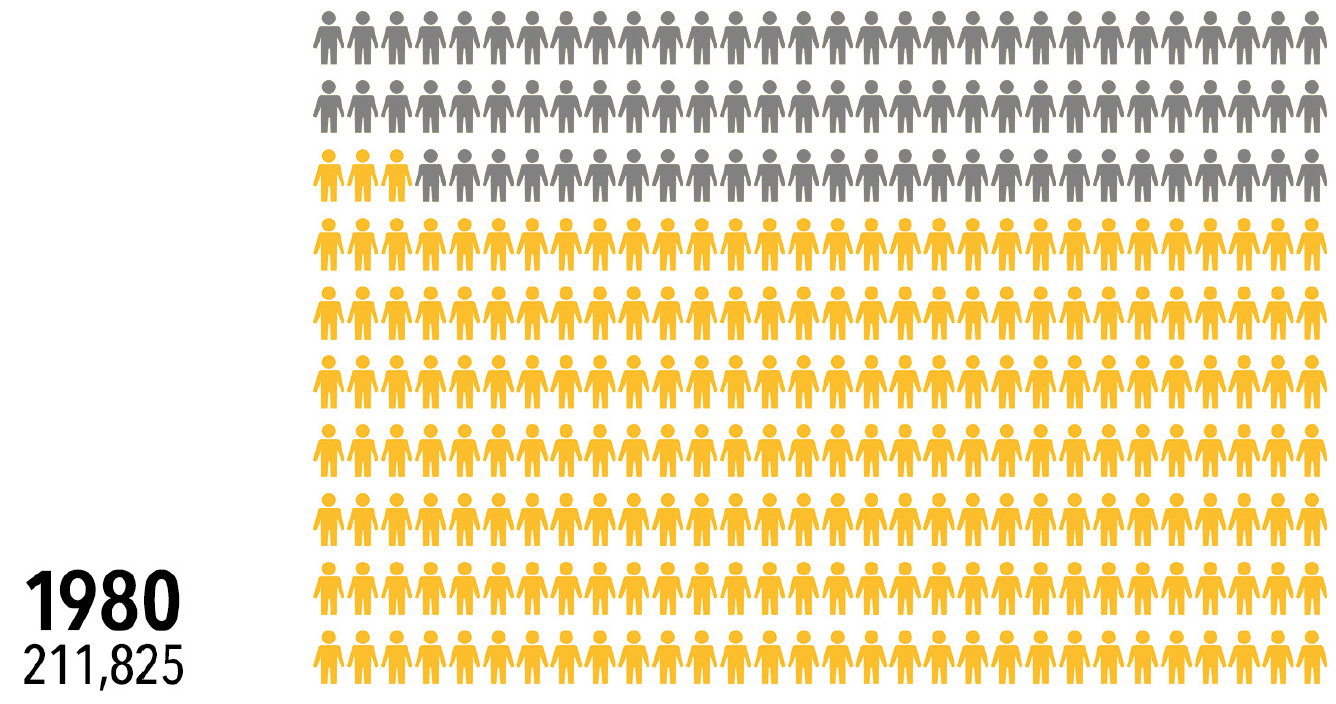

It was during another school expansion project in the 1960’s that Detroit reached a turning point. Enrollment peaked at 299,962 students in 1966 and then began to steadily decline.26 A school district that had struggled to keep apace of growth almost continuously for 124 years was suddenly faced with a new crisis: shrinking.

The automobile plants that fueled the growth of the city began to move to the suburbs in the 1950’s, taking with them jobs and tax revenue. “White flight” had begun, leading to an exodus of parents and students from the city into the surrounding metropolitan area. 15,000 students left the school district between 1966 and 1971,27 even as construction finished on new buildings. The parents leaving the district took with them tax dollars badly needed by the schools and the city. The loss of students also decreased state funding for Detroit schools, which are given a fixed dollar number per student enrolled. Each student leaving cost the district thousands of dollars in revenue that had been counted on to pay for recent construction and modernization, leaving the district carrying the cost of more buildings than it needed, as well as the very recent construction costs associated with building them.

At the same time, district administrators struggled to keep up with changing social attitudes. The Civil Rights movement marked the beginning of the end of Detroit’s de facto school segregation, and court-mandated “bussing” programs that brought black students to what had been mostly white schools led many parents to withdraw their children from the public schools, accelerating the decline in enrollment.28 This began a downward spiral of enrollment, reduced funding, and disinvestment in schools, which led to further enrollment loss.29

As enrollment began to fall in the 1970’s, the school district faced a new problem: for the first time since its founding the district had more classroom seats than it had students. While some parts of the city were still growing, others had begun to shrink, leaving some schools more than half empty. New school construction all but stopped, as the district instead turned its efforts towards keeping as many schools open as possible. Recognizing that the school was often the social and civic center of a neighborhood, many schools were kept open despite being far below capacity. This practice, while maintaining neighborhood stability, was not sustainable in the long term as neighborhoods began to empty out, and enrollment continued to fall.

Parents protesting bussing of black students to mostly white schools.

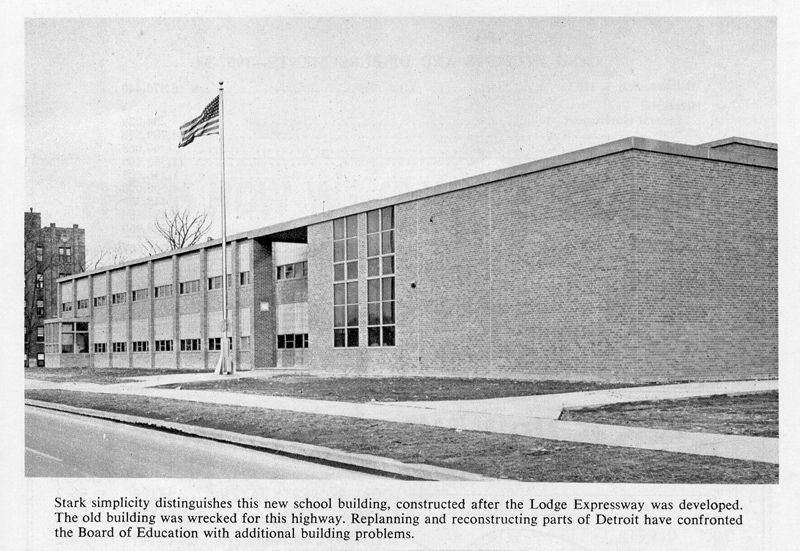

Fairbanks Elementary, one of 28 schools built in the 1950’s. The annual report notes the difficulty facing the school district in rebuilding.

Early Closings

Prior to the 1970’s, most school closures were related to replacement of existing buildings, clearance for industrial and housing projects, or downsizing schools in neighborhoods that were losing population. The first major wave of closures came in 1976, as 14 mostly older schools were closed to comply with court-ordered desegregation policies. In 1982, enrollment fell below 200,000 students, and 15 more schools were closed as part of a district-wide reorganization. Nine schools closed at the beginning of the 1990 school year.30

Though these closures were heatedly opposed by some residents,31 they reflected the reality that the district could no longer sustain the large number of school buildings without bleeding district finances dry.32 Neighborhood schools built just a decade or two prior suddenly found themselves with far fewer students than seats, as the neighborhoods around them slowly emptied out. The population freefall, when combined with a 50% decline in birth rate between 1990 and 2007,33 left fewer children enrolling in school at all.

In the midst of this, a lack of strong, decisive leadership by elected school officials undermined public support for the school district. As early as the 1930’s, the school board fell prey to political and special interest groups,34 leading to frequent leadership changes and clashes between members. As elected officials, board members could be recalled or voted out at any time, making them slow to respond to the changing social landscape. Public trust was lost as it emerged in the 1970’s that board members were spending significant amounts of taxpayer money on travel expenses and chauffer-driven cars.35

As allegations of misuse of funds made front-page news, the union representing Detroit Public School teachers sought wage increases that would bring their pay more in line with nearby school districts.36 Detroit teachers were among the lowest paid in the state, but paying for the wage increases often came at the expense of fully funding the school system, which was forced to operate at a deficit. When sides failed to reach an agreement, teachers would go on strike; walkouts in 1967, 1973, 1979, 1982, 1987, and 199237 ranged from a few days to six weeks.

Preston School, which closed in 1982 and had been vacant for years when this picture was taken. Library of Congress.

Teachers went on strike for a variety of reasons. Though pay was often cited as the main cause, teachers were also protesting the deteriorating conditions in schools. Deferred maintenance meant that repair work on schools was delayed or simply not done, leaving older buildings in especially poor condition. In March of 1987, a large section of the ceiling in a classroom at Condon Middle School collapsed while students were at lunch. No one was injured, but the entire third floor of the 74-year old building was evacuated until engineers could evaluate all of the classrooms.38 Condon closed just two years later.

Especially damaging was a 1992 strike by Detroit teachers, which lasted four weeks and made headlines around the country as educators defied a judge’s order to return to work.39 By the following year, the district had lost 15,384 students, over 9% of total enrollment.40 Though enrollment stabilized and recovered slightly through the 1990’s, the school district never fully recovered, as public education in Michigan was undergoing a significant transformation that would have wide-reaching consequences in years to come.

A Board of Education employee inspects the damage at Condon Middle School after the ceiling collapsed in 1987.

Teachers on strike in the fall of 1987.

A Changing Academic Landscape

Frustration with the state’s public education system grew as strikes shut down schools for weeks at a time across Michigan through the 1980’s and 90’s.42 43 Calls for reform led to the Michigan legislature passing two acts in the 1990’s that would dramatically alter the state’s educational landscape.44

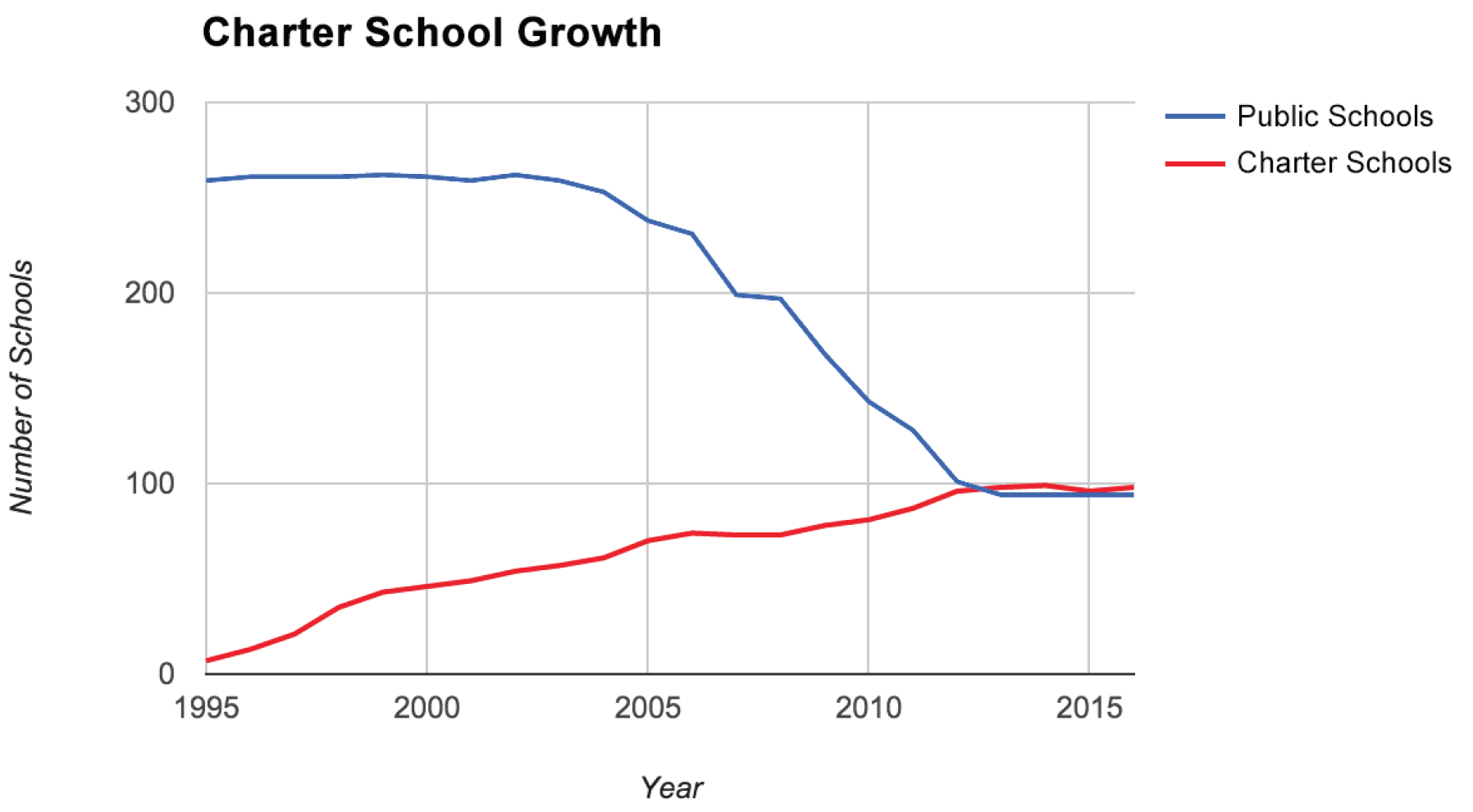

In January of 1994, the State of Michigan authorized the creation of “Public School Academies,” better known as charter schools, which are privately-run schools that can receive state funding. Charter schools are considered an alternative to public schools, with which they compete directly for students and per-student funding.45

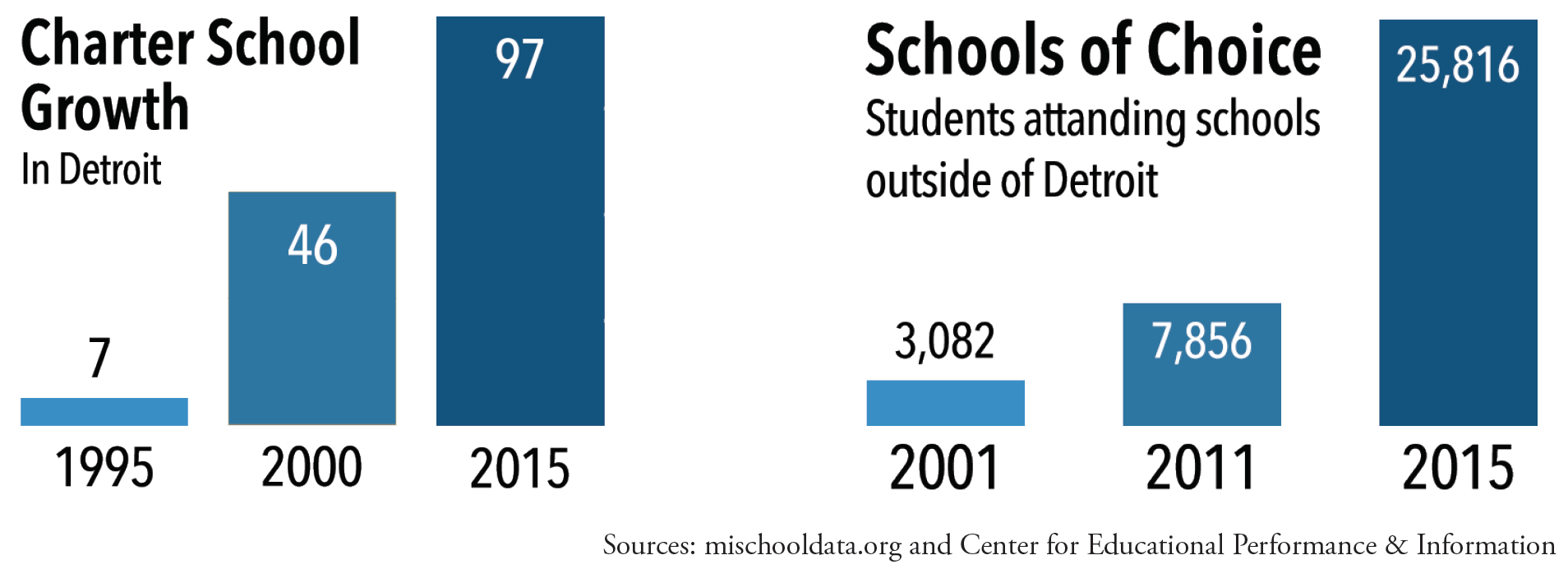

The growth of charter schools in Detroit closely matches the decline in the number of public schools. From an initial 14 charter programs in 1995, an average of 7 new charter schools have opened every year since.46 By 2001, over 19,000 students were enrolled in charter schools in Detroit.47 As DPS closed schools, charter operators began to expand their offerings to attract DPS students, advertising in areas where the schools were closing.48 The number of charter school students in Detroit grew to over 51,000 by 2013, eclipsing the number of students enrolled in Detroit Public Schools, which had fallen below 50,000.49

"During the 1990s and continuing into the present, declining student enrollment has drained resources away from DPS at an alarming rate. The financial impact of declining enrollment coupled with reduced state funding has created a severe crisis for DPS."

— 2003-2004 School District Improvement Plan

As of 2014, there were 96 charter school programs operating in Detroit, compared to 103 public school programs.50 Forty-seven charter schools are located in former Detroit Public School buildings, all of which were sold or leased from 2000 to 2015.51 Twelve of these schools are now run by the State of Michigan under the Education Achievement Authority, a charter system which took over some of the city’s lowest-performing schools.52 Another public act passed in 1996 and expanded in 1999 loosened restrictions on where students could attend schools, allowing students to attend school districts outside of the one they resided in, and for the receiving schools to receive the per-pupil funding.53

Under “schools of choice,” Detroit parents could send their students to suburban public and charter schools, which would then receive the funding that previously would have gone to Detroit Schools. In 2011 alone, Detroit lost 7,856 students to other school districts, or 10% of its total enrollment.54 By 2015, over 25,000 students were attending public and charter schools in districts outside of Detroit.55

Consequences

The impact of these programs became clear in the late 1990’s when enrollment in the district - which had been increasing slightly - leveled off in 1998 and began to decline. Where DPS had added 3,084 students in 1996-97, the district lost 5,635 students in 1999-2000, and another 5,520 students in 2000-01.56

The immediate impact on DPS was financial. Each student that left for another district took $6,402 in state funding with them.57 The loss of 11,155 students in two years cost the district $71.4 million dollars out of the general budget - money that had been planned for and already spent. Budgets carefully planned for a certain number of students had to be hastily revised mid-year, cutting programs and positions.

Starting in 2002, per pupil state aid remained flat, even as expenses increased, compounding the financial losses. When adjusted for inflation, state funding actually decreased by $2,208 per pupil from 2002 to 2013.58.

In the midst of staff layoffs due to the budget crisis, overtime costs rose in 2002 from $2.5 million dollars to $14.8 million.59 Some of the first positions to be cut were in non-teaching positions. Fifty out of 271 district social workers, who worked with the most difficult and at-risk children, were laid off in 2002. “This type of thing will come back and haunt the district,” one school psychologist told the Detroit Free Press.60

A sign advertising River Rouge Schools posted in front of Mark Twain Elementary, a DPS school that closed in 2009.

The financial problems came in the midst of a massive school construction and modernization program, as construction began on the first new schools built in over 20 years. Altogether 12 new schools were opening or under construction by 2002,61 just as DPS began losing students and funding. While new schools were welcomed by parents, the condition of older schools and course offerings deteriorated as finances got worse.62

"Closing school buildings is a painful process for students, staff and communities that leaves everyone feeling devastated and without hope. That is probably why the District has been unable to adequately deal with its current state of over capacity. Nevertheless, closing school buildings has become a necessity for many districts experiencing enrollment declines. For Detroit Public Schools, closing schools is absolutely essential to its survival.”

— Preliminary Facilities Realignment Plan For 2007-2009

What it Means to Close a School

The decision to close a school is a controversial, complex, and costly process. It impacts every part of the education system, from students to teachers to the neighborhoods around the schools and the city as a whole.

For many years, DPS avoided closing schools in large numbers, maintaining a large network of increasingly underutilized neighborhood schools for fear that closing them would lead to parents leaving the district.64

As recently as 2000, the district had 287 school buildings, housing 162,693 students. To close the budget gap, the district began closing underutilized and poorly-performing schools, consolidating students into fewer buildings.

The Process

School building closings usually happen for several reasons: low academic performance, utilization, and building condition. Schools with consistently low test scores may close and reopen with a new program, or transfer students to nearby schools with higher test scores. Underutilized schools, some at less than 50% of the building's intended capacity, are expensive to operate. Some school buildings, particularly older ones, are in poor condition due to deferred maintenance, making them unsafe for occupancy or prohibitively expensive to repair. Oftentimes, the rationale for closing a school is a combination of these factors.65

Choosing which schools to close was a difficult and controversial process. A facilities report published by the district in 2007 noted that

“...unfortunately, students do not leave in groups of 25, 30 or 35, or whole school buildings. As a result, District costs for staff and facilities cannot be reduced to correlate directly with student loss. Classrooms that drop from 30 students to 20 cost the same to operate even though they produce one-third less revenue. Buildings that lose 20-40% of their students continue to have the same fixed costs for utilities, maintenance and school based administration but produce less revenue.”66

This meant that even while funding decreased, the cost of maintaining buildings went up. The small neighborhood schools built in the 1950’s and 60’s were especially at risk, with higher per student costs and locations that could only serve small areas:

“More school closures are necessary but neighborhood schools are often trapped between highways, major roads, and industrial areas creating significant pedestrian and student transportation obstacles.” 67

Between 2000 and 2003, DPS closed and merged 15 schools.68 Most were smaller, older schools in poor parts of the city that had struggled for years and faced possible closure before. McMillan School, built in 1895 and located in an industrial neighborhood in southwest Detroit had narrowly avoided closing in 1993, but closed in 2001 with just 300 students.69 Angell Primary, which closed the same year, was the smallest school in the district with just 69 students in a building designed for 115.70 Some, like Schulze and Howe Schools were replaced by new buildings, 16 of which opened during the same time period.71

In the midst of the closings, the district struggled with overcrowding in some schools as parents moved within the city to other neighborhoods. 72 In June of 2003, 35 schools were at 75% capacity or less, while 67 were at 125% capacity or over.73

For parents, the closing of a neighborhood school was often the breaking point in a long, frustrated relationship with the school district. Program cuts and the closure of some of the city’s oldest schools sparked a backlash from parents and educators, who fought to keep low-enrollment but high-performing schools open. Protests by parents became so disruptive in 2002 that the district looked into moving the meetings to smaller locations, or broadcasting them by closed circuit television in another room.74 One parent told a Detroit Free Press reporter during a meeting about the closure of Burroughs School in 2003, “I’m sick of it. I’ll take my kids out of school.”75

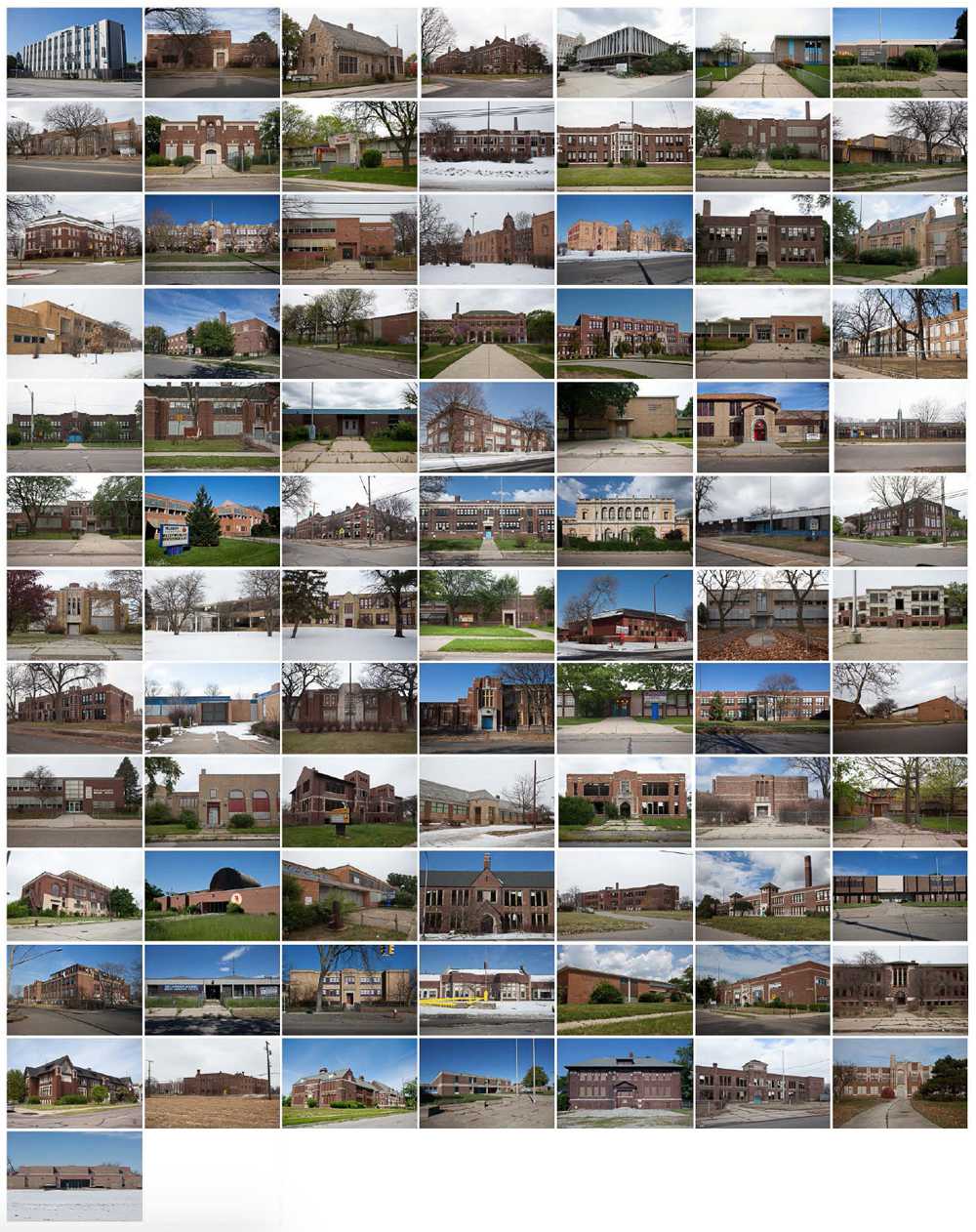

All of the schools that closed between 2000 and 2015 — click to open the full gallery

The Hidden Costs of Closing Schools

As the decade wore on, the enrollment crisis in Detroit Public Schools deepened. Over 9,000 students left DPS during the 2004-05 school year, as a budget surplus was wiped out and the district began running a deficit that would balloon to nearly $600 million dollars by 2010.76 Further closings did little to slow the exodus; six schools closed in 2005, followed by 26 more schools in 2006.77

"We now have half as many students as we did in 1970 and nearly the same number of buildings... From a cost standpoint, it doesn’t make sense. With these school closings, our district will become more efficient and more effective."

— Detroit Public Schools CEO Kenneth Burnley to the Free Press, 2005

However, the anticipated financial benefits of the school closings were not nearly as significant as predicted. Oftentimes, the predicted cost savings of closing schools one year were wiped out the next as even more schools closed, and unanticipated expenses piled up. In the Preliminary Facilities Realignment Plan For 2007-2009, the district outlined how closing schools would save the district nearly $19 million dollars a year annually in facilities upkeep. The report cautioned, however, “little or no savings will result in the first year of the plan. That is because the District will incur one-time costs for moving materials from the closing buildings, boarding up and securing the closing buildings, and making modifications in a number of the receiving schools to accommodate new grade configurations…”79 In fact, after one-time closing costs and increased transportation costs, the closings would cost the already cash-strapped district an additional $5,000,000 for the first year.

The scope of the closings was difficult for the district to manage. A 2008 report by the Council of the Great City Schools found that

“...the district has no capacity for long-term planning and its operations are largely transactional in nature… No long-range master facilities plan exists. The school district has largely avoided closing underutilized schools or has done so with inadequate criteria or analysis. It has no strategy to assess the value of or to sell its excess space.”80

Despite a shortage of supplies throughout the district, millions of dollars in textbooks, furniture, and computer equipment were left in schools that closed between 2005 and 2007. After a 2008 article in the Detroit Free Press brought the issue to light, DPS spent an additional $4.5M cleaning out and securing over 30 closed schools, filling a warehouse the size of a football field with abandoned supplies. Custodians, bus drivers, and kitchen workers worked for months to empty out buildings, costing the the district over $1 million dollars in overtime.81 82

In some cases, large amounts of money were spent reconfiguring schools to receive fewer students than before. Hutchins Middle School, an underused but academically successful school was closed in 2007 and its 372 students relocated to McMichael School, located over 20 blocks south of the old location. The district then closed a nearby school for students with special needs and moved them into the Hutchins building.83 The massive school, built in 1921 with a designed capacity of nearly 2,000 students, had to be renovated and partitioned off because large parts of the building were not needed for the 289 students it was receiving.

Supplies left behind at Joy Elementary School, which closed in 2007.

The special needs program at Hutchins closed just two years later in 2009 due to low enrollment, leaving the building vacant. McMichael, the school that had received Hutchins students, closed in 2011 for the same reason. Over half of the Hutchins students, unable or unwilling to travel the long distance every day through rough neighborhoods and gang territory went to different schools or transferred to charters.84

The rapid pace of closures and lack of planning also meant that some schools closed just years after substantial renovations or additions. Between 1999 and 2012, over $78 million dollars was spent upgrading schools that later closed. Another $27 million dollars was invested in schools that were closed and demolished a few years later.85 Sherrard Elementary was renovated in 200286 at a cost of $1.4 million dollars, only to close in 2007. By 2005 $3.9 million had been spent on new athletic fields at Redford High School,87 which closed just two years later. The athletic fields continued to be used by the community until the school was demolished in 2012 to make way for a commercial development.

Accelerated Closings, Instability, Disruption

By 2006 the district was losing over 10,000 students a year, and the number of school closings that year jumped to 26.88 The rapid pace with which schools closed meant that some students attended four different schools in four years.89 Closings and consolidations that had affected only a few thousand students three years ago now impacted over 10,000 students every year.90 With fewer schools to choose from, students began walking longer distances to school, often through dangerous neighborhoods that lacked streetlights.91

Closing high schools was especially problematic. Most of the city’s high schools were large, sprawling campuses designed in the 1920’s and 30’s for thousands of students. With graduation rates of only 56% and a dropout rate of nearly 30% in 2007,92 high school students were at especially high risk of leaving the school system if buildings had to be closed or consolidated.

Mackenzie and Redford High Schools were the first two major high schools to be closed in 2007. Parents and school officials worried that transferring students to rival high schools would spark gang violence.93 Three years later when Cooley High School was facing closure, one student recalled “when Redford closed, a bunch of them came here and it led to a bunch of different fights… It’s just going to get worse.”94 Some students dropped out rather than finish out their education at a rival high school.

The closures, intended to save money, instead accelerated the decline of the school district. Each closing brought new protests, more parents removing their students from the district, and corresponding decreases in enrollment and funding.95

Emergency Management in Detroit

An emergency financial manager can be appointed by the State of Michigan to take over the operations of any local government unit, like a city or school district that is in financial trouble. First used in 1988, emergency managers have become increasingly common as cities around Michigan have struggled with deindustrialization and economic recessions. The cities of Detroit, Highland Park, Pontiac, and Flint have had emergency managers take over for periods of one to nine years, depending on the severity of the financial crisis.158

The State of Michigan has taken over control of Detroit Public Schools twice. In 1999, the district was taken over in response to growing concern about financial and educational stability,137 and the elected school board was replaced by one appointed by the mayor.138 Though the board was reinstated in 2005, it continued to struggle with financial problems until the state intervened again in 2009 by appointing an emergency financial manager to take over the school system.139 140

The district’s first emergency financial manager was Robert Bobb, a former president of the Washington D.C. school board.159 Bobb moved quickly to rein in spending, outsourcing jobs and cutting positions throughout the district while boosting efforts to increase enrollment. In his first year as emergency manager, Bobb predicted that the district would see a $17 million budget surplus. However, spending actually increased so much that by January the forecasted surplus was replaced with a $98 million deficit for the year.160 By the end of his two year term, the deficit had grown to over $284 million dollars, 59 schools had closed, and the district had lost over 20,000 students.161

Emergency managers have had a mixed record of success in Michigan. Successes have been small: Muskegon Heights School district has cut its deficit from $12 million dollars down to $1 million since the appointment of an emergency manager in 2012.162 The village of Three Oaks avoided bankruptcy after a year spent under an emergency financial manager.163

Highland Park, a city inside of Detroit under emergency management from 2000 to 2009, has struggled to remain solvent after control was returned to elected officals.164 When the city’s public school district declared a financial emergency in 2012, the state appointed Jack Martin as emergency manager.165 A year later, management of the district was turned over to a private charter group, and Martin had left to take over the position of emergency manager for Detroit Public Schools. Highland Park Schools lost over 50% of its students and closed its high school as successive emergency managers struggled to balance budgets.166

Detroit Public Schools has had a total of four emergency managers since 2009, none of whom have been able to stabilize the school district or its finances.167 During the 18 months Jack Martin was the emergency manager in Detroit, the deficit increased from $82 million dollars to $170 million.168 Enrollment has fallen by over 50% since the state took over the school district, down to just over 47,000 students.169

Current DPS emergency manager Darnell Earley left his position as emergency manager of the city of Flint in 2015, where he had served for two years.170 It was under Earley’s leadership that Flint made the disastrous switch from Detroit’s water system to the Flint River,171 which has been linked to elevated levels of lead and a deadly outbreak of Legionnaires' disease.172

Consequences: After Closing

More than a decade into the closing and consolidation program, the impact of disrupting the lives of students by closing schools on enrollment is becoming clearer. 2012 saw the closure of 32 schools, up from 17 the year before. The district lost over 15,000 students that year, over 23% of the remaining population.96 In 2013, the district closed only six schools “in recognition and support that our schools are the center of our neighborhoods.” No schools closed in 2014 or 2015, despite continued, but smaller enrollment losses.

For students, it has meant constant uncertainty about where they will be going to school at the beginning of the next year. Every change of school meant new teachers, new rules, and new educational practices. Students have to walk further, or be bused to distant, unfamiliar neighborhoods.

By 2015, enrollment in Detroit public Schools had fallen below 50,000 for the first time in over 100 years.

Friends that grew up across the street from each other might suddenly find themselves on opposite sides of an attendance border and sent to different schools.97 This instability and uncertainty caused students to go elsewhere for education. District studies found that when schools were closed or moved, they lost 30% of enrollment, significantly reducing the cost benefits of shuttering the school.98

It is also clear that a facility's expenses don’t end when a building is closed. One-time costs to secure a building are about $100,000, and $50,000 a year per building to maintain. Water pipes, if not maintained, freeze and burst during the winter, flooding the schools. Constant break-ins required repairs and stretched the district’s police department thin. By 2007, DPS was spending over $1.5 million dollars a year maintaining vacant schools.99 The cost of maintaining so many vacant buildings was so high that in 2011, emergency manager Robert Bobb considered “simply abandoning” the closed buildings, a move that would have saved $12.4 million dollars.100

A key cost-saving rationale was that once the buildings were closed, they would be sold or otherwise disposed of, reducing long-term financial burdens on the district. But the closure of so many school buildings in a relatively short time span has also left the district with a large amount of surplus buildings and real estate, much of which is located in declining neighborhoods far outside the city center.

Steel security panels installed over the windows and doors of the closed Fairbanks School.

Detroit Public Schools Police arrest metal thieves who had been stripping windows out of the closed Hutchins Intermediate School in the background.

Between 2000 and 2015, 195 Public Schools in Detroit Closed.

Of the 288 schools that started the 2000-2001 school year, only 93 remain open today. The rest are either vacant, have found new uses, or been demolished.

Vacating Schools

The most common outcome is that a closed school is left vacant. There are currently 82 vacant school buildings in Detroit. Another 35 schools were vacant for long periods of time before being demolished.106

Vacant schools are especially problematic because of the speed with which they fall into disrepair. As routine maintenance stops, nature begins to work its way into the building. Leaking roofs allow water to penetrate deep into the building, causing plaster to dissolve and the growth of mold. Freezing temperatures cause paint to flake off the walls, and wood floors warp as moisture builds up.

The most destructive force, however, is human. As the district began to close schools in 2003, the value of scrap metal, particularly copper, was on the rise as demand in China outstripped production. Across the country there was a surge in metal theft as “scrappers” stripped copper pipe and wiring from vacant buildings. Detroit was hit especially hard; the price of copper went from $0.77 / pound in 2003107 to over $4.00 / pound in 2008108 as dozens of schools were closing and left vacant. Older buildings in particular were rich in copper, as pipes, flashing, and even entire roofs were made of solid copper. Scrapping is a lucrative business, where someone with limited education or job skills can make hundreds of dollars a day, depending on the building.109

Most schools closed between 2000 and 2004 had simply been padlocked after the last day of school. As break-ins became more common, DPS stepped up patrols, began using heavy steel panels to cover windows, and installed motion-sensitive wireless security cameras in closed schools.110 The cameras caught many scrappers in the act, but once they learned to recognize the cameras, they would smash them faster than the district could replace them.

In just a few days, scrappers could strip out the copper pipes and wiring from a school, leaving gaping craters in walls and water gushing through broken pipes111 112 113. As a result, most vacant buildings are in extremely poor condition and would require significant investment to reopen in any capacity.

Hallway at Cooley High School, which closed in 2009. Paint begins flaking off due to fluctuations in temperature after the heat is turned off.

81 Schools Vacated

Out of the 195 schools that closed between 2000 and 2015, 81 are currently vacant and unused.

What Happens After Closing?

Nearly all of the 81 vacant school buildings that Loveland surveyed in 2015 and 2016 had suffered damage from scrapping at some point since they closed. 34 have fire damage.

Many more school buildings were open to trespass until the fall of 2015, when ownership of 50 school buildings was transferred from the school district to the city. Since then, at least 30 schools have been partially or completely boarded up as part of a building trades program with local construction companies.

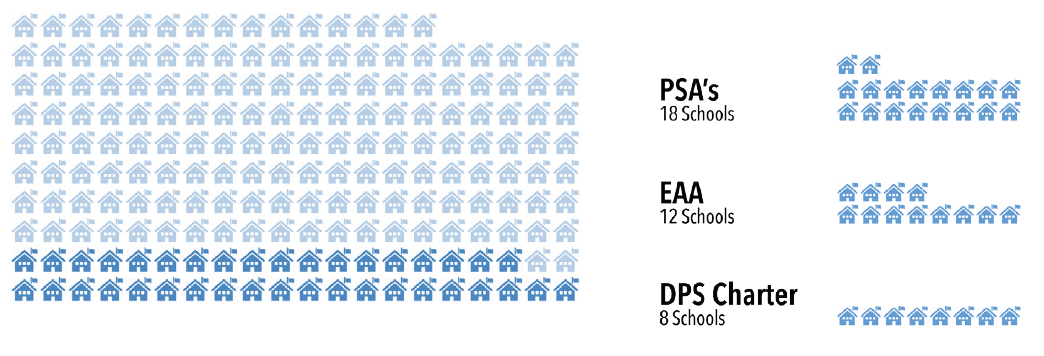

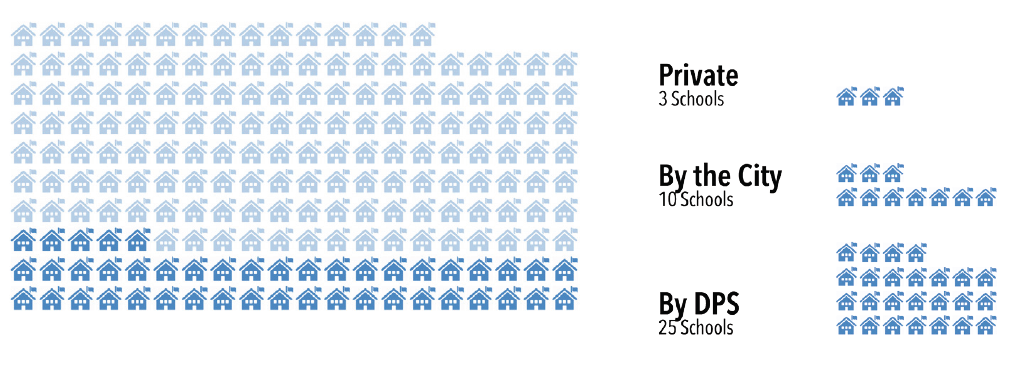

Charter Schools

The growth of charter schools in Detroit has come at the expense of the public school district. As DPS has closed schools, the number of charter schools has increased.

Between 2000 and 2015, 38 charter schools opened up in former Detroit Public Schools buildings. 18 of these schools were Public School Academies, which make up the majority of charter schools in the city.

Twelve of the lowest-performing public schools were transferred to a state-run district in 2012. Though the buildings are still owned by DPS, they are operated by the state of Michigan.

Eight schools have become charter schools run by DPS.

As the number of active public schools has declined, the number of charter schools has increased.

The Detroit Enterprise Academy, a charter school on the east side of Detroit located in a former Catholic School.

38 Charter Schools

Reuse

Reuse is the ideal outcome for a closed school building, but is complicated by several factors: Unlike retail or office buildings that can be easily repurposed into something similar, schools are purpose-built for education. Their layouts are sometimes complex as a result of multiple additions over the course of many years. Many of the buildings are more than 60 years old, and in poor condition after years of deferred maintenance. As most schools closed due to low enrollment, their locations are in neighborhoods that are far from ideal for educational reuse.

The sheer number of vacant school buildings in Detroit has made it difficult to find buyers. The first school closings in 2003 came at a time when there was already a glut of educational property on the real estate market. Many parochial schools had closed in the years before,102 leaving little demand for buildings that were old, needed extensive repairs, and were located in challenging neighborhoods.103 A study by the Pew Charitable Trusts found Detroit Public Schools had 124 vacant schools or parcels of land for sale in 2012, over four times as many as the next closest district.104

Prospective buyers face additional hurdles. In 2012, the district’s real estate office had just two employees tasked with disposing of over 100 properties. A lack of information about the buildings for sale, including their floor plans and current condition make it difficult for buyers to know what is available and what sort of investment is required.

Some of Detroit’s closed schools have reopened as residential apartments, community centers, churches, and in one case, a theater. Paradoxically, one of the key players in declining enrollment - charter school operators - are the biggest customer of closed schools, buying or leasing 51 former public school buildings from the district, 38 of which closed between 2000 and 2013.105

The gymnasium of Miller High School, a historic building that closed in 2007. The school was later renovated and reopened as a charter school.

32 Schools Repurposed

Demolition

Vacant schools are a drain on the community around them, attracting scrappers, drug dealing, and prostitution. They quickly become eyesores, bringing down the property values of nearby houses.

Demolition is often a last resort, when a school is no longer worth saving and has no future value. The costs of demolition vary by school; some larger high schools cost upwards of $1M to $3M to abate and demolish114 115, while smaller elementary schools cost around $300,000.116 This is a cost not factored into the financial savings of closing a school.

For many abandoned schools, the level of damage caused by scrapping is serious enough that they will have to be demolished.117 Between 2000 and 2015, 35 abandoned schools were demolished, while our survey indicates that at least 28 currently vacant school buildings are in such poor condition that they need to be demolished.

Ten schools were demolished to make way for replacement schools.

Cass Technical High School being demolished in 2011.

45 Schools Demolished

Comparing Detroit’s School Closings to Chicago

Detroit is not the only major city school district facing closures and consolidations: Pittsburgh closed 22 schools in 2006; Washington DC closed 23 schools in 2008.118

Like the City of Detroit, Chicago, IL has struggled with large-scale school closures. Between 2001 and 2012, Chicago Public Schools closed 90 of its 601 schools119 120 as the population of the city declined and enrollment fell.121 Another 49 schools closed at the end of the 2012-13 school year, the single largest number of school closings in the United States, eclipsing Detroit’s 31 school closures the same year.122

CPS has faced many of the same challenges as Detroit: the introduction of charter schools has drawn students away from the public school system, while its lowest-performing schools have been transferred into a privately-run entity. A large number of closed school buildings have had to be disposed of, with many of the same location and condition complications that Detroit has.

While Detroit has struggled to find uses for its surplus buildings, Chicago has had more success. Of the 90 schools that closed between 2001 and 2012, only four schools have been left vacant. 35 reopened as public schools with different academic programs, or merged with other nearby schools. 41 became charter schools. Five were sold are now used for non-education purposes. Three were demolished due to poor buildings conditions. Several schools were phased out over the course of a few years to minimize disruption to student life, and closed after the last class graduated.

However, the 2012-13 closings have proven to be more problematic. Of the 49 schools that closed in 2013, only seven have been sold or repurposed for non-academic uses. 32 schools are currently vacant. Efforts to maintain and secure the large number of vacant buildings have run into the same problems as Detroit. Water was left on at several shuttered schools, which froze and burst over the winter, causing serious water damage. Scrapping has taken it’s toll as well.123 A visual survey of all vacant school properties in November of 2015 found that 16 schools had boarded windows and other signs of intrusion. 14 schools appear to be in poor or distressed condition. Significantly, though, none of the schools were open to trespass.

Many of the most recently closed schools are located in struggling neighborhoods. Though some charter school operators have expressed interest in reopening some of the closed schools, Chicago’s teachers’ union have fought any further growth of the charter system at the expense of public schools, and the agreement to close schools had stipulations that they not be reused as charter schools.124

In late 2013, Mayor Rahm Emanuel set up a committee to address the problem of the closed facilities. A plan released in early 2014 recommended implementation of a three step process to reuse or dispose of closed buildings that involved consulting with the community.125 If no viable use is found for the schools by 2016, the committee recommends demolishing the buildings.126

How Did It Get to this Point?

Detroit’s public school system has closely followed the trajectory of the city: Rapid growth, followed by an equally rapid decline. For over 125 years the school district had too many students, and not enough schools. For the past 30 years the district has had too many schools, and not enough students. Through the 1970’s and 80’s, DPS lost students, mostly as a result of people moving out of the city. The introduction of charter schools and schools of choice in the 1990’s completely changed the academic playing field, as DPS faced competition for students for the first time. The rapid loss of students to charter and suburban schools, combined with cuts in state funding left the district scrambling to reorganize itself, chasing budgetary and enrollment goals that slipped further out of reach each year.

As DPS began closing schools in the early 2000’s, poor planning and financial decisions meant that some schools were receiving multi-million dollar upgrades just a few years before closing. The unprecedented number of school closures and consolidations as well as the frantic pace with which they were carried out left student life in a state of turmoil, leading to further departures from the district.

Buildings that were closed were not secured properly, and in some cases, left full of supplies and equipment needed at other schools. The closures coincided with a sharp increase in the value of scrap metal, leading to many of the buildings being stripped of everything of value. Some buildings were so badly damaged that they required demolition, adding to the district’s financial woes.

Suburban Schools

Detroit isn’t the only city experiencing a decline in public education.

Public school districts all around Detroit and the state of Michigan have closed schools in the last 20 years. From their peaks in the 1990’s, three nearby school districts have closed over half of their buildings. Each city has struggled to manage their closures.

The Future

Detroit Public Schools faces a no-win scenario.

Enrollment will continue to decline, as the city population drops and parents opt to send their kids to charter schools or other districts outside of the city. The loss of per-pupil funding will exacerbate an already dire financial situation, simultaneously increasing the budget deficit while reducing the amount of money available for education and facilities upkeep. Maintenance on aging school buildings will be deferred in the short term, leading to costly issues like leaking roofs and broken boilers in the long term. With no additional money, Detroit’s 1,700 teachers can expect no substantive pay raise, leading to a further exodus of experienced, dedicated teachers from the district and a corresponding increase in classroom size. As the quality of education and facilities decreases, more students will leave the district, and already underutilized buildings will empty further.

Faced with the high financial cost of maintaining schools with only half of the students they were designed to accommodate, the district will be faced with a stark decision: close / consolidate the lowest performing schools, or maintain them at reduced levels despite the increased cost. Neither outcome is viable in the long term. Studies have found that the district loses about 30% of students when it closes or moves a building, which would diminish any cost benefits of closing and financially cripple the district. Leaving underutilized buildings open will do little to stem the flow of students out of the district and likewise do irreparable harm to the school district’s financial situation.

Left unchecked, this cycle of student loss and school closure will continue until the district is no longer economically viable, leading to its collapse within the next two years barring major intervention at the local or state level.

Intervention may come in the form of competing plans to reform the school district that have been proposed by Gov. Rick Snyder of Michigan and Mayor Mike Duggan, both of which would see

the district split in two, with one “shell” district assuming the debt, and the other to operate the remaining public schools. But state intervention hasn’t worked in the past.

The State of Michigan has taken over control of Detroit Public Schools twice. In 1999, the district was taken over in response to growing concern about financial and educational stability,137 and the elected school board was disbanded.138 Though the board was reinstated in 2005, it continued to struggle with financial problems until the state intervened again in 2009 by appointing a state emergency financial manager139 140 to take over the school system.

Further state intervention came in 2012, when twelve of the lowest-performing public schools in Detroit were transferred to the Education Achievement Authority (EAA), a state-run charter school district tasked with turning around troubled schools.141 Launched amid much fanfare, the EAA has struggled with low test scores, severe drops in enrollment, mismanagement,142 and is now regarded as “a botched experiment that further destabilized Detroit schools.”143

The cumulative effect of state intervention has been questionable. Despite improvements in test scores, under state-appointed executives and emergency managers, the district’s deficit has risen while enrollment has dropped to its lowest level since 1884. The lack of public say in school matters has eroded confidence and support in the district by residents, who feel disenfranchised and are less invested in the success of the school district.

Under state management, Detroit Public Schools has moved to the brink of financial and social insolvency. Enrollment is expected to continue to decline by at least 2% through the 2015-16 school year,144 while charter schools in the city increase their enrollment.145 Of the $7,296 per student funding the district is receiving this year from the state, $3,019 is going towards paying off existing debts instead of instruction costs. Long term debts for the district top $3.5 billion dollars. To start the school year, the district had to borrow $121 million dollars from future state aid to fund payroll, and will likely require further loans to before the school year is over.146

An ongoing teacher shortage, fueled by retirements amidst uncertainty about the future of the district and stagnant wages, has left schools understaffed with 170 job openings.148 The Detroit Institute of Technology, one of three programs at Cody High School, had only one math certified math teacher to teach 300 students before she quit in November of 2015.149 Over the winter of 2015-16, teacher “sickouts” caused schools to close on multiple occasions, spreading from just a handful of schools in December to over 60 on January 11th.150 Among the concerns cited by teachers were overcrowded classrooms with 45 students, buildings infested with black mold, and lack of security guards.151

The sickouts are one of the few ways that Detroit teachers can express their frustration with the current situation,152 but could backfire if frustrated parents decide to remove their children from the district. The unannounced closures have disrupted the lives of tens of thousands of students and their parents153, who may be attracted to the relative stability of charter and suburban schools. If just a few thousand students leave DPS, the financial impact would likely lead to the collapse of the district within the next year.

What Can Be done

Instability - in the form of schools closing, programs moving, financial crises, and poorly-performing schools - is a major factor in students leaving the district. If the Detroit Public Schools system is to survive, it requires immediate intervention to stabilize and reorganize itself into a viable entity.

DPS’s debt crisis must be addressed. Debt service payments are eating into funds that should be used for instruction and building upkeep. The district will need to find a way to downsize the number of schools it has without causing serious disruptions to student life, causing them to leave the district. Another round of school closings will trigger a further exodus of students to charter schools and nearby school districts, sapping badly needed funding from the already struggling school district.

Under better financial conditions it may be possible to “phase out” schools in a similar manner to that of Chicago, closing them over a period of years to allow students to finish at them and minimize disruptions. During the phase-out, school buildings could be more effectively marketed to potential buyers, who would be better prepared to take over the building immediately after closing and avoiding periods of vacancy.

All of these measures will be for naught unless the steady loss of teachers to early retirement and other districts can be brought under control. Attracting high-quality educators requires offering competitive wages, competent management, and a positive working environment.

“We’re running out of money in April… We need help to fix the school district once and for all. Our kids deserve a good education and when you don’t have cash there are things that are lacking.”

— Marios Demetriou, Deputy Superintendent Finance and Operations to the Detroit News, 2015147

Conclusion

What happened to Detroit Public Schools?

From its founding over 150 years ago, Detroit Public Schools had been at the forefront of academic development, pioneering new ways of teaching and educating as the city expanded rapidly through the 19th and 20th centuries. Crisis is not a new thing; the district has jumped from one crisis to the next for most of its existence, first struggling to provide enough schools for the booming population, to then having too many schools but not enough students. Through all these years, students and administration have dealt with a city in constant transformation, two world wars, racial turmoil, economic depression, and a changing society.

There is, however, no precedent in the past for dealing with the current crisis the district faces. The fundamentals of public education have changed over the last 20 years, as competition in the form of charter and suburban schools has left public school districts scrambling to catch up. DPS’s failure to adapt to the changing educational environment has had serious consequences, including the loss of over 100,000 students and the closure of nearly 200 schools in the last 15 years. The district faces a deeply uncertain future, as enrollment, funding, and teacher morale plunge.

There are no easy answers. The most immediate concerns are financial, but local and state officials are hesitant to bail out a school district that has demonstrated such poor control over money in the past. And even if money were available, it would take years to address the immediate issues that the district faces, like repairing buildings and restoring funding to teachers and programs. Can the district maintain enough enrollment to make this investment worthwhile?

Judge Stephen J. Roth, in a ruling regarding the desegregation of Detroit’s public schools in 1971 wrote that “there is enough blame for everyone to share.”154

In his eyes, the school board, the city, and the state had actively worked to keep the school district and city segregated, and failed to adapt to the changing social tide sweeping across the nation. Jeffery Mirel used the quote for the title of a chapter of his book The rise and fall of an urban school system: Detroit, 1907-81. Roth’s words still ring true today, as blame for the current state of Detroit’s schools gets bounced between the teachers, the administration, the state, and the city.

A desire to avoid blame has created a morass of inaction that keeps DPS in a protracted state of crisis, bleeding students and funding while others argue about who did what. The barriers that have been built by administrations, unions, and bureaucrats to protect their own interests have to be broken down. Every day that passes without action is a lost opportunity. Every year of inaction is a lost generation of students, deepening the already severe inequality between the residents of the city and those of the suburbs around the city.

It wasn’t so long ago that the city of Detroit was viewed as a lost cause. Today, neighborhoods throughout the city are starting to bounce back as residents take control of their future. The process is not complete, and the city will continue to struggle with vacant properties and inequality for many years to come. But innovation - municipal, commercial, and individual - is driving significant change.

A critical question that must be answered by both the residents of the city and the government is: are Detroit’s public schools worth saving? And if so, how?

If Detroit Public Schools is to have a role in the rebirth of the city, it must innovate too. The district needs fresh ideas, solutions, perspectives beyond what we have now. DPS has faced challenges in the past, and risen to meet them.

Pay What You Want

We made this independent report because we thought it was important. If you agree, please share it and consider contributing $1 or more. If we reach $25,000, we'll keep doing more work like it. If you have questions or would like to commission a report on any topic, email us at team@makeloveland.com. Thank you, and please enjoy.

A Note About Accuracy:

While every effort has been made to ensure the quality and accuracy of the information as presented in this report, there may be mistakes or omissions that were not found prior to publishing.

In the course of researching this report, some sources of information conflicted with others sources due to differences in methodology. Record keeping methods has changed over the 174 years that the district has kept them, leading to differences in enrollment counts, school names, and number of active schools. In each instance where primary sources conflict with each other, we have evaluated each and chosen what we believe is the most consistent and accurate data.

For some schools, especially older ones, we have been unable to find accurate information about when a school closed or was demolished due to lack of records. These are noted as such.

We welcome feedback and questions: help@regrid.com

Data:

Detroit Schools 1842-2015 master sheet

Enrollment:

There are two different primary sources for enrollment data: The State of Michigan’s MI School Data Portal (Center for Educational Performance and Information, 2015), and the Detroit Public School’s annual financial reports. There are differences in annual enrollment between the two sources of a small amount, with DPS’s count labeled as “K-12 Student Membership for Funding Purposes.” We use the DPS count numbers for two reasons: they are used in other documents put out by the school district, and the data goes back to 1992, where the MI School Data Portal only goes back to 2003. The three primary documents used are the 2003, 2007 and 2014 Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports, pages 4 and 8 respectively.

Spreadsheet Sources:

Histories of the Public Schools of Detroit volumes 1-3 provided detailed narratives of basically every public school in Detroit up until the 1960’s and was the primary source for our research.

Proceedings of the Board of Education, Detroit These are summaries of regular meetings held by the Board of Education and covered every aspect of education, including building plans and construction. The detailed notes in these proceedings cleared up many inconsistencies brought up by different sources, providing clear dates and locations. While Hathi has only a small part of the 1900’s in their digital collection, the Detroit Public Library and the Reuther library have volumes dating back to the 1860’s, and all the way up through 1986. These were used extensively.

Annual Report of the Detroit Public Schools Also known as the Superintendent’s Reports, these were yearly summaries of the happenings of the school district that date back to it’s founding. The Detroit Public Library has volumes going into the 1930’s, but these large annual reports had largely been discontinued by the 1940’s in favor of promotional brochures.

Directory and by-laws Each year the board of education published an internal booklet of all school locations and offices, dating back to 1896. Older volumes listed the name, address, year of construction, and additions. The Detroit Public Library has over 100 volumes of these yearly directories from 1896 to 1999, which we digitized and used for reference in geolocating schools and roughing out timeframes when schools opened or closed.

ProQuest The ProQuest digital newspaper archives includes complete daily issues of the Detroit Free Press from 1831 to 1922. The archives contained detailed information about all aspects of the schools, including when they were built.

Public education in Detroit Provided much information about the early organization of the school district.

Financial Data & Reports The comprehensive annual financial reports from 1996 to 2014 are an excellent source for school capacity and status.

Sanborn Maps These highly detailed fire insurance maps date back to the 1870’s and were updated through 1996. Sanborn maps were especially helpful in geolocating some of the early schools, as the street naming and number system changed considerably in the 1920’s, making most address listings from before then obsolete. They also had limited value in establishing when additions were made to schools, but had some accuracy issues with specific dates.

Google Earth With historic aerial imagery going back to 1999, Google Earth was used to narrow down timeframes for when schools were built or demolished. In a few cases, the imagery showed construction and demolition in progress, definitely establishing these dates.

Street View - Google Maps As above.

Bing Maps As above.

DTE Aerial Photo Collection These high-resolution aerial photos range from the 1940’s to the 1990’s, and played a critical role in narrowing down the timeframes of construction and demolition dates.

EarthExplorer Another aerial photograph source which filled in some gaps that the DTE Aerial Photo Collection did not have.

NETR Online Another aerial photograph source which filled in a significant gap in the early 1970’s.